As New Orleanians, I think it’s common for us to think of Martin Luther King Jr. as a national hero, working in far-off and distant cities. His message and his accomplishments no doubt shaped us and our hometown, but — as an instigative pastor in Birmingham or a leader in the fight to end the segregation of Montgomery’s public bus system — we’re more likely to consider him a part of those places than NOLA.

But that started to change for me this past MLK Day. Then-mayor, Mitch Landrieu, was addressing a crowd in A.L. Davis Park on Lasalle Street in Central City. He said, “Dr. King was physically right across the street. We are not in some far away and distant place. We are at the place where it started.”

Here? I hadn’t even known King had visited New Orleans. My interest was piqued.

MLK Comes to NOLA

In January of 1957, looking to scale their success with Montgomery buses all across the South as well as to move toward the full desegregation of public facilities, 60 black ministers and leaders, including King, met in Atlanta under the not-short-but-quite-descriptive name, “Southern Leadership Conference on Transportation and Nonviolent Integration.” The SLCoT&NI (I made that acronym up, but…c’mon) sent President Eisenhower a letter requesting he come to the South to place “the full weight of his office” in demanding local police protect all citizens and enforce law and order indiscriminately. When Eisenhower declined their invitation, the organization announced a follow-up meeting here, in New Orleans, and issued a press release including the following:

“It is ironic that less than three weeks ago millions of dollars were spent on an inaugural ceremony [for Eisenhower]. The climax of which was the oath by President Eisenhower “to uphold the Constitution of the United States.” We Negro leaders from 29 communities and ten states ask for nothing more than this…and we ask for it here, in the South, and now.”

Their New Orleans meeting was set for the following month — on February 14 — but first King would travel to our city to address its residents.

The previous day, he met with Clarence “Chink” Henry, president of International Longshoremen’s Association Local 1419, an all-black union, as part of King’s goal to increase pay and improve working conditions for African-Americans. He spoke at the union’s hall, which is now the Capital One Bank at 2700 S. Claiborne Avenue.

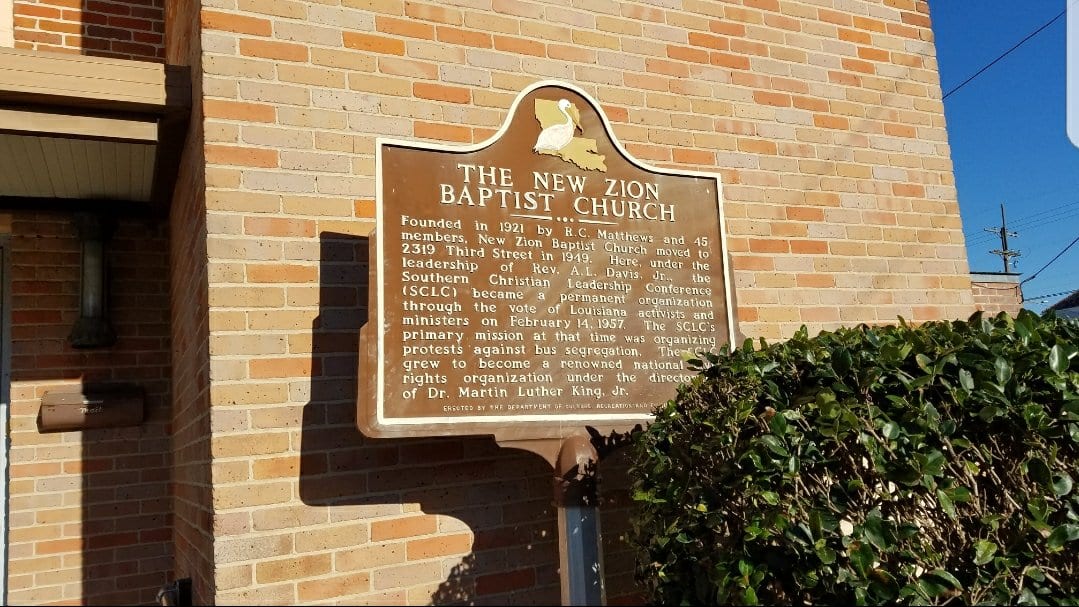

Just two weeks later, on Valentine’s Day in 1957, King and 96 other black religious leaders of 35 communities from 10 states met in Central City — across the street from where Mayor Landrieu would address the crowd I was in 60 years later — to plan their next steps in pressuring the federal government to act in favor of desegregation. They met inside the New Zion Baptist Church on Third and LaSalle streets where members officially founded a national organization — still in existence today — with a much more manageable name: the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC).

King was elected the organization’s first president that day. “Segregation,” he told the group in a close-door session, “was a great cancer in the body politic.” And their mission was to end it.

New Orleans Helps to Send MLK to Washington

During segregation in New Orleans, it was illegal for black and white patrons to dine in the same restaurant. But one still-famous Treme restaurant, Dooky Chase, with a well-hidden staircase leading up to an inconspicuous second-floor dining area, made it possible for leaders of the Civil Rights Movement, regardless of race, to meet, eat and plan together.

It’s unclear whether MLK Jr. ever stopped in for these meetings.

“He was a man that didn’t sit down,” owner Leah Chase said in a 2016 interview with WGNO. “I’d feed the freedom riders, we’d sit down, and we’d talk. But he wasn’t like that. He was always on the move.”

Whether or not he was there, we know numerous local and national Civil Rights leaders dined and strategized on his behalf, including Thurgood Marshall, Dutch Morial, Reverend A.L. David, Oretha Castle Haley, and his father, Martin Luther King Sr. Together, they planned many of his sit-ins, marches, boycotts, and freedom rides.

The movement strengthened, and – through failures in Albany, Georgia, to sit-ins in Birmingham, Alabama; from marches in St. Augustine to illegal gatherings in Selma; from trips to India to Freedom Rides toward New Orleans — King’s SCLC had emerged as a leader.

And at that Valentine’s Day meeting in Central City, he emerged with a promise — a second letter to President Eisenhower, signed by King, that read, “In the absence of some early and effective remedial action, we shall have no moral choice but to lead a Pilgrimage of Prayer to Washington.”

As he prepared to give his speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, on August 28, 1963, witnesses say they heard New Orleans’ own Mahalia Jackson implore King to “tell them about the dream you had.” And, famously, that’s what he did. In front of the 300,000 in attendance, as well as the countless more who will listen to it, members of every generation from that one until humanity’s end.

MLK’s Likeness (Kind of) Returns to New Orleans

Today, New Orleans has — not one, but two — monuments to King. How’d that happen?

The first is on the corner of Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and Oretha Castle Haley Boulevard, the perfect location for a statue pertaining to the Civil Rights movement and its leaders. But the statue itself is not what you’d expect from a monument to King, mostly because it doesn’t look anything like King. Or a human, for that matter.

Standing 10 feet tall and created by Frank Hayden of Southern University in Baton Rouge, it kind of looks like if an octopus and an egg had a baby…and then the tentacles were given human hands with long, elegant fingers.

A States-Item reporter wrote, in 1976, when Mayor Moon Landrieu pulled a cord to unveil the statue, reactions were mixed. While some said they liked it, “photographers hesitated, children stared wonderingly, and most of the 200 or so residents of the Dryades-Melpomene area…did a double-take.”

Hayden explained his work was meant to symbolize “Dr. King’s lifelong quest to bring people together to achieve understanding.”

Today, many residents see it as a monument to life, hope, and the coming together of disparate cultures. But at the time, the statue was so unpopular among some prominent black radio personalities and civil rights leaders, there was an effort to raise money for a new, more straight-forward statue.

A 1978 newspaper ad read, “King was a Man!” and continued, “Let’s remember Martin Luther King as he was to all people of the world. Please support the Martin Luther King Memorial Statue Fund.”

The

This second New Orleans monument was a replica of one created in Selma, Alabama, with the inscription, “I Had a Dream.” Organizers, here, however, decided that — even though King was killed in Memphis on April 4, 1968, his message would not meet the same fate. His dream would continue, and the statue was edited.

MLK’s Legacy in New Orleans

When Mitch Landrieu spoke of this city’s history with King and the movement he led, he was speaking primarily about the past. But there are exciting and important steps being taken to this day that help keep King’s legacy and mission alive.

The SCLC — the organization he founded here — revived a chapter in New Orleans, and they are active with a lecture series, the sharing of history, monthly meetings, and a plethora of volunteer opportunities. Check out their website!

Additionally, a block away from the New Zion Baptist Church, an ambitious nonprofit, Felicity Redevelopment, Inc., owns two empty lots and – in collaboration with the SCLC, Tulane University, and Central City churches, schools and neighbors – they are designing and building a commemorative pavilion that will provide educational information, a contemplative space, and a public gathering area honoring the founding of the SCLC and the broader Civil Rights movement. The project will also include the development of a curriculum focused on the civil rights history of the LaSalle Street Corridor for nearby schools.

Felicity’s Executive Director, Ella Camburnbeck, said, “As a community, we can decide what stories, people and places we choose to lift up and memorialize.”

And perhaps there’s no better story to elevate than our contribution to the life of Martin Luther King Jr. and his historic fight for the equal rights of all Americans.