If you spend time around Bayou St. John, you may have noticed that Magnolia Bridge (aka “Cabrini Bridge,” once known as “Bayou Bridge” or “Old Bayou Bridge) is back in action — rust replaced with a new coat of blue paint!

The renovations — which took about a year to complete — involved replacing many parts of the bridge, exchanging damaged wooden boards with a surface made of composite materials, stabilizing the bayou’s banks, installing a cable-barrier system, and several repairs to the bridge’s structure.

All in all the upgrades cost $1.3 million, but it also meant a Bayou Boogaloo, Jazz Fest and a summer of recreation without access to this community gem.

But now — with relatively little fanfare — the bridge is back! I happen to like fanfare though, and if any bridge deserves it, it’s this one.

So I thought it would be fun to take a brief look back at the history of this Bayou St. John landmark.

19th-century infrastructure

On a warm, spring afternoon, I walk to the middle of the bridge and watch as Bayou St. John curves around a bend where downtown skyscrapers poke out behind ancient Spanish moss-laden oak trees. In the other direction, deep gray clouds shaped like thought-bubbles converge on some point over City Park. Like the clouds, the bayou also flows that way — toward Lake Pontchartrain.

It’s in that direction that this bridge’s story began.

In the late 1800s, the bridge I’m standing on was originally erected on Esplanade Avenue, over Bayou St. John, less than a quarter-mile from where it currently rests. It’s confusing, but here’s what I know:

This Magnolia Bridge’s current location – between Cabrini High School on one bank and Hardin Drive on the other – used to be occupied by a different footbridge. On the school’s side of the bayou, there was a picnic area called, “Magnolia Gardens.” In 1884, the name was changed (depending on who you asked) to “Southern Park.” In the 20 years between 1890 and 1910, the park often hosted popular band performances. Because of the bridge’s proximity to Magnolia Gardens, it was also sometimes referred to as Magnolia Bridge, as was the case in this amazing article about a duel-gone-wrong.

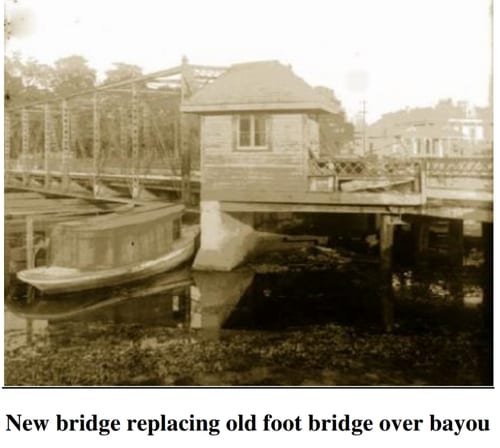

As mentioned above, the bridge we now call Magnolia Bridge (when we’re not calling it Cabrini Bridge), was built on Esplanade Avenue and was frequently called Bayou Bridge or, eventually, Old Bayou Bridge. This bridge included one set of streetcar tracks, making it accessible to public transportation, but also to pedestrians, horse-drawn carriages and automobiles.

(Note: There was a third “Magnolia Bridge” that crossed what was formerly the New Basin Canal at Magnolia Street, near what is currently the Smoothie King Center. That canal was functional from the 1830s through the 1940s, and the bridge was a launching point for freight and passenger ships, as well as the site of hundreds of 19th and 20th-century murders. But this is a story — and a bridge — for another day. Now, back to our current Magnolia Bridge.)

A game of musical bridges

In 1906, with both streetcar and automobile traffic increasing, and with the Canal-Esplanade streetcar belt switching to heavier cars, some city officials were concerned the aging, one-lane, wooden structure wasn’t enough. A July 27 Times-Picayune article from that year documents a debate over the safety of the bridge. The paper reported the testimony of local expert and member of the Park Commission, Mr. A. Blais, to the Streets and Land Committee:

“He had even complained of the use of this bridge by the lighter cars, but now that the great, heavy cars had been put on the Belt Line, these cars were frequently taxed to carry 100 persons at a time over that bridge. He believed that the foundations at the ends of the bridge would give way one day when a car was upon the bridge and good-by for everyone who was in the car, for they would be screened in without the least possible chance of getting out of a window. If one of those large cars of the Company should go through that bridge into the bayou no one could escape except possibly some on the back platform – they would be drowned like rats in a trap.”

It was decided a steel bridge, wide and strong enough to hold a double streetcar track (basically, to allow for easier two-way traffic) should replace what Blais called our old “menace.” But, before old Bayou Bridge could be demolished, the city chose to move the bridge down the bayou to Grand Route St. John.

At the time, Bayou St. John was part of the Old Basin Canal (aka the Carondelet Canal) — a waterway that hosted frequent shipping traffic. Even though Bayou Bridge rotated at its center — turning itself parallel to the bayou so ships could pass on either side — the severe bend in the bayou at Grand Route St. John would make navigation difficult, prompting the Canal Navigation Company to reject the city’s proposal to move Bayou Bridge there.

But a compromise was found right here at Harding Drive, the site of that old pedestrian bridge (since widened to allow for carriage traffic) near Southern Park.

The plan was to destroy that smallest bridge (the former Magnolia Bridge that had been there at the time of the aforementioned duel), then to blow up its foundation on each bank of Bayou St. John. Bayou Bridge would be lifted from its foundation at Esplanade Avenue, placed on a barge (!) and floated down the waterway to its current location, where it would be re-erected. A new, stronger bridge would be placed at Esplanade Avenue, and everyone would be happy.

The plan was going swimmingly! *wink* Bayou Bridge was successfully relocated, and at some point, took on the name Magnolia Bridge (but also, sometimes, Cabrini Bridge).

But then the plan stopped going swimmingly. A May 19, 1909 article from the Times-Picayune documented what happened when the new, stronger, steel replacement bridge was lowered during a stress test at Esplanade Avenue:

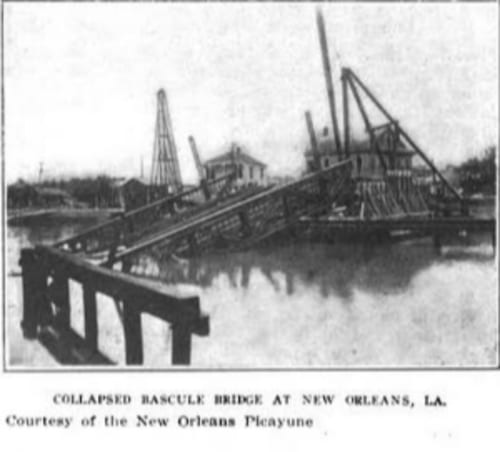

“With a terrific crash, the span of the steel bascale trunnion bridge in the course of construction at the Esplanade Street end, crossing Bayou St. John, snapped in twain, and the heavy superstructure fell into the bayou, effectually closing navigation of the waterway for some time to come. Five men were injured, one of them, Frank Cunningham, fatally.”

Meanwhile, the “menace” survived.

A bridge to the modern era

Though the Esplanade Avenue bridge met its demise, Magnolia Bridge was safe and sound. For the next few decades, I don’t believe Magnolia Bridge was used for streetcar traffic, though furious residents clamored for it every time something went wrong with the replacement bridge on Esplanade Avenue.

In a Jan. 2, 1911 edition of the Times-Picayune, one streetcar passenger responds sarcastically (and surprisingly contemporarily) when they learn the Esplanade Avenue bridge is stuck in the “up” position. “Well, how am I to get across Bayou St. John to board a Canal belt car?” he asked. “I suppose it’s up to me to rent a skiff or motorboat?”

The conductor fought sarcasm with kindness by pleasantly informing the frustrated passenger that it would only be a few blocks walk to cross the Magnolia Street bridge and link up with the streetcar on the other side.

In the 1920s, the Old Basin Canal was closed to shipping, which meant Bayou St. John’s primary purpose would now be recreation. In 1936, during the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration stabilized and restored Magnolia Bridge, this time without the ability to rotate for passing ships.

I watched cars drive up and down Moss Street, vanishing around a bend on their way to Esplanade Avenue, or turning onto Grand Route St. John. I tried to imagine what it would have been like for a queue of old automobiles on each side of the bridge as they waited their turn to cross the narrow structure.

Over the next three decades, the bridge fell back into disrepair. In 1971, it was closed to vehicular traffic because of safety concerns, and in April 1972, a group of schoolchildren were walking across the bridge when a small girl fell through, into a space where two wooden boards were missing.

(In the bridge’s defense, what in the world was she looking at? This is way before we were all looking down at our cellphones!) Luckily, her friends were able to pull her back up onto the bridge, and – as the girl’s parents wrote in a strongly worded letter to the Editor of the Times-Picayune — “crisis was averted.”

Somehow, even after that near-disaster, Magnolia Bridge wasn’t restored again until 1989.

The bridge is back

Thirty years later — in 2018/19 — it was time for another repair.

And it’s no news to anyone who lives in New Orleans, but we love that bayou and we love that bridge. A few months before the rehabilitation project began, then-City Councilmember, Susan Guidry, told The Advocate, “It’s really the only waterway we have within the city that draws people to its banks to use, whether its families having picnics or the festivals we now have there…For those of us who like to walk, run and bicycle, it connects our neighborhoods.”

As I stand on the bridge and watch the bayou rush toward Lake Pontchartrain to eventually link up with the Gulf of Mexico, I’m reminded it also connects us to the rest of the world.

And, finally, as a woman pushes her baby in a stroller across the bridge’s newly finished surface, it’s easy to see how landmarks like this one also connect generations. More than 100 years of New Orleanians have special Magnolia Bridge moments: from first dates and first kisses; to birthday parties and crawfish boils; to thoughtful strolls and quiet moments.

Welcome back, Magnolia Bridge, and we look forward to another century of special memories.

Writer Matt Haines lives in New Orleans. Follow him at matthaineswrites.com and on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.